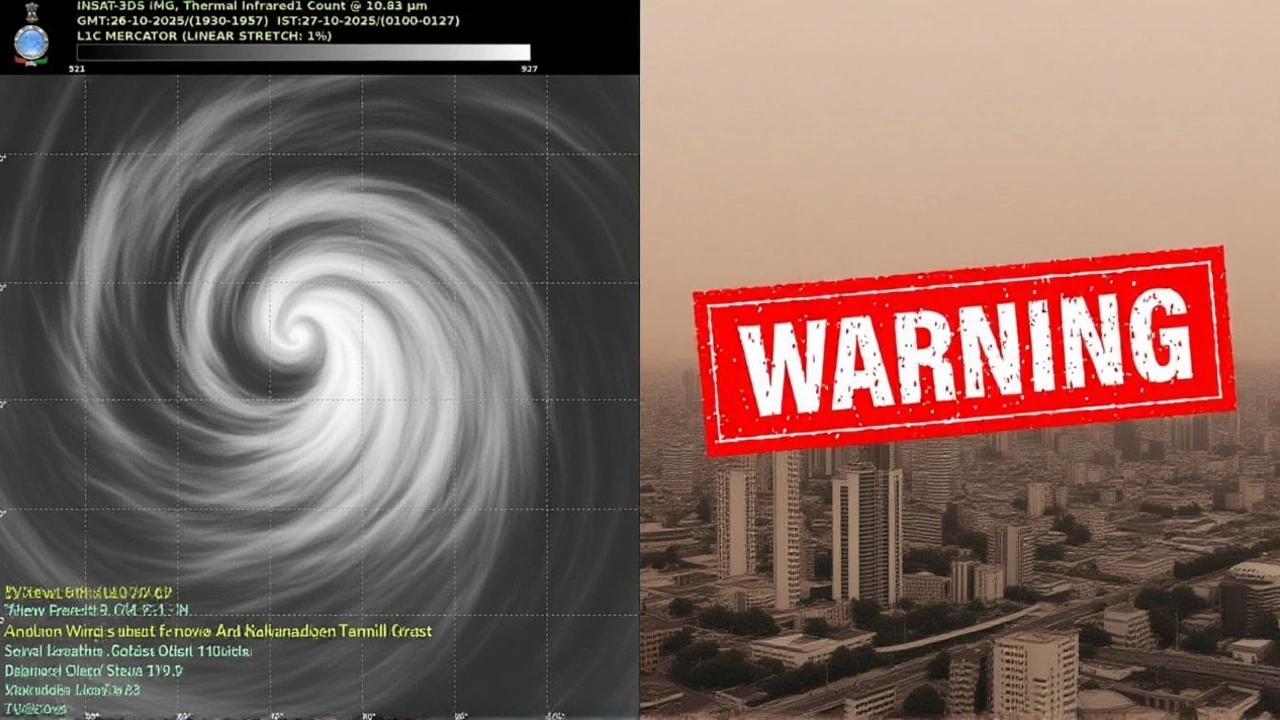

Cyclone Montha Bears Down on Andhra Coast with 110 km/h Winds, Triggering Nationwide Emergency Response

When N. Chandrababu Naidu woke up on October 27, 2025, the wind outside his office in Amaravati was already picking up — not just a seasonal breeze, but the first real breath of Cyclone Montha. By nightfall, it would be roaring at 110 kilometers per hour, poised to slam into the coast between Machilipatnam and Kalingapatnam, just north of Kakinada. The India Meteorological Department (IMD) had warned: this wasn’t just another storm. It was a severe cyclonic storm, building fast, with rain so heavy it could dump over 20 centimeters in 48 hours. And it wasn’t stopping at the shore.

From Low Pressure to Landfall: How Cyclone Montha Formed

It started quietly — a low-pressure area swirling over the Bay of Bengal on October 24. By the 26th, satellite images showed it tightening, spinning faster, drawing moisture like a vacuum. The IMD upgraded it to a cyclonic storm on the 27th, and by dawn the next day, it was expected to become a severe cyclonic storm. That’s not just meteorological jargon — it means sustained winds of 100–110 km/h, gusts higher, and a storm surge pushing seawater a full meter above normal tide levels. Coastal villages near Kakinada are bracing for water to flood streets, homes, and rice paddies alike. The timing? Evening or night on October 28 — when most people are home, lights are on, and power grids are most vulnerable.Government in Motion: Coordination Across Levels

By 10 a.m. on October 27, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had already spoken with Chief Minister Naidu. The call wasn’t ceremonial. Modi pledged immediate central support — relief funds, NDRF teams, air logistics. Within hours, Nara Lokesh, Andhra’s IT Minister, was in direct contact with the Prime Minister’s Office, coordinating digital alerts and drone surveillance over flood-prone zones. Meanwhile, in Delhi, Jagat Prakash Nadda, central BJP president, ordered state units in five states to turn party offices into relief hubs. Workers were told: distribute food, set up medical camps, clear debris before the rain even stops. The National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) deployed 22 teams — 14 in Andhra Pradesh, 5 in Odisha, 3 in Tamil Nadu. Each team carries inflatable boats, medical kits, and thermal imaging gear to find people trapped in rooftops or submerged homes. In Odisha, officials didn’t wait for requests. They pulled 100 stranded fishermen from Andhra waters and housed them in schools turned shelters. “We didn’t ask who they voted for,” said an Odisha relief officer. “We asked if they had warm clothes.”Trains Stopped, Schools Closed, and the Silent Inland Threat

South Central Railway canceled 54 trains — not just those heading to the coast, but routes through Guntur, Nellore, and even parts of Telangana. Indian Railways axed another two dozen nationwide. Schools in 12 districts of Andhra Pradesh shut early on the 27th. Hospitals moved critical patients to higher floors. But here’s what most headlines miss: the storm’s reach goes inland. The IMD warns that Chhattisgarh, hundreds of kilometers from the coast, could see wind gusts over 80 km/h. Trees will fall. Power lines will snap. In Uttar Pradesh, dense clouds already brought intermittent rain on the 27th — a sign the cyclone’s outer bands are stretching north, feeding into the monsoon’s lingering moisture.

What’s at Stake: More Than Property

This isn’t just about damaged roofs. Andhra Pradesh produces nearly 15% of India’s rice. The Krishna and Godavari deltas — the breadbasket of the state — are directly in the path. Farmers who planted just weeks ago could lose entire crops. Fishermen, who make up 7% of the coastal population, have no income if their boats are wrecked. In Yanam, a small Puducherry enclave, saltwater intrusion could poison wells for months. And with heavy rainfall expected to last until October 30, drainage systems — already clogged and outdated — will buckle. The IMD predicts 15–20 cm of rain in places like Krishna and Guntur districts. That’s more than the average monthly rainfall for October.What Comes Next: The Long Recovery

Landfall is just the beginning. The real challenge begins after the winds die down. Power restoration could take days. Clean water will be scarce. Disease outbreaks — especially waterborne illnesses like cholera — are a real concern. The state government has pre-positioned 1.2 million liters of drinking water and 800 metric tons of food. But logistics will be a nightmare. Roads are already flooded in low-lying areas. Helicopters will be needed. And the federal government? It’s promised ₹3,000 crore in immediate relief, but rebuilding will take years. Experts say this storm is a preview of what’s coming more often: stronger cyclones, fueled by warmer seas. The Bay of Bengal warmed by 1.8°C above average this year. That’s not coincidence. It’s climate.

What the IMD Isn’t Saying (But Experts Are)

The official forecast says “heavy rainfall” — but it doesn’t say where the worst pooling will occur. Local hydrologists point to the lower Krishna basin, where embankments haven’t been upgraded since the 1980s. “We’ve seen this movie before,” says Dr. Priya Menon, a climate researcher at IIT Madras. “In 2018, Cyclone Gaja hit the same stretch. We rebuilt the roads. We didn’t rebuild the drainage.” Now, with Cyclone Montha, those old failures are magnified. The state’s early warning system worked — but the response infrastructure didn’t keep pace.Frequently Asked Questions

How is Cyclone Montha different from previous storms like Gaja or Fani?

Unlike Cyclone Fani (2019), which hit Odisha with 200 km/h winds, Montha’s strength is more localized but slower-moving, meaning prolonged rainfall over Andhra’s fertile deltas. Compared to Gaja (2018), it’s stronger in wind and rain volume, with a storm surge higher than any since 2001. Its unique threat is inland penetration — Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh aren’t typically cyclone zones, but this one’s outer bands are pushing that boundary.

Why are 54 trains canceled in Andhra Pradesh alone?

The South Central Railway routes through coastal Andhra run parallel to the shoreline, where flooding can wash out tracks and damage signaling systems. Canceling trains preemptively avoids stranded passengers and reduces rescue risks. Trains are also used to transport relief — so keeping them idle ensures they’re ready when needed, not stuck in floodwater.

What’s the role of the BJP’s state units in disaster response?

BJP workers are acting as local coordinators — not replacing government efforts, but filling gaps. They’re using their neighborhood networks to identify elderly residents, distribute water packets, and report blocked roads. In villages without mobile signal, party volunteers are the first to relay damage assessments to district headquarters. It’s an informal but critical part of the emergency chain.

Is this cyclone linked to climate change?

Yes. The Bay of Bengal’s sea surface temperature this year is 1.8°C above average — the warmest in two decades. Warmer water fuels stronger, wetter cyclones. Studies from IIT Delhi show cyclones forming in this region are now 30% more likely to reach severe intensity than they were in the 1990s. Montha fits that trend: rapid intensification, heavier rain, longer duration. This isn’t an anomaly. It’s the new normal.

How long will the rainfall last, and where’s the worst impact?

Heavy rain is expected from October 27 through October 30, with the peak between the 28th and 29th. Krishna, Guntur, and West Godavari districts are at highest risk for flooding and crop loss. The Yanam region, though small, faces saltwater contamination of freshwater sources — a long-term threat to drinking water. Even inland districts like Kurnool and Nalgonda may see flash flooding from runoff.

What should residents do if they’re still in flood-prone areas?

Stay off roads. Do not attempt to drive through water — just 15 cm can sweep away a car. Keep emergency kits ready: flashlight, bottled water, medicines, phone charger. Charge devices now. If told to evacuate, go immediately — don’t wait for official orders. Call 1070 (state emergency line) or use the ‘Andhra Disaster Alert’ app for real-time updates. Avoid contact with floodwater — it may carry sewage or live wires.